Slices

Next time you look at a dataset, here are a few ways to consider slicing it to find a noteworthy positive deviant. This table is not meant to be exhaustive, but rather to spur your imagination a bit. For more on the Slices approach, see the Core Toolkit.

| Strategy | Description | Health Example |

|---|---|---|

Change Over Time | Which place has made newsworthy improvement? | Riverside Med Center drastically cuts infection rates KPCC |

Comparison to Peers | Which place is doing better than its comparable peers? | Latinos Live Longest Despite Poverty. Here’s Their Secret Yes! Magazine |

Method/Best Practice | Which place is succeeding with innovative new ideas? | Why doctors are prescribing legal aid for patients in need PBS NewsHour |

Coverage | Which place has greatly expanded access to a solution? | Minnesota program embeds therapists in schools The Post Crescent |

Subgroup | Which place has improved outcomes for a particular population? | FDA’s ‘terrible policy error’ blocks simple step to prevent fatal birth defects The Seattle Times |

Policy | Which government has instituted successful new policies to solve a problem? | The City That Unpoisoned Its Pipes Next City |

Disparity | Which place has reduced racial, geographic or socioeconomic disparities in outcomes? | Detroit Team Shrinks Breastfeeding Disparities Women's E-News |

Cost | Which place has maintained good service while reducing costs? | Busting the billion-dollar myth: how to slash the cost of drug development Nature |

Time | Which place has managed to deliver a service or achieve a desired outcome in less time? | Wait Times Improve; Telemedicine in Play

Rio Grade Sun |

Basic Cheese Pizza | A basic small slice of the problem. Kids’ consumption of fruit and veg - a small slice of obesity. | Fruit, Not Fries: Lunchroom Makeovers Nudge Kids Toward Better Choices NPR |

Evidence Introduction

How do I find the “best” solution to any health problem?

This one’s easy. You don’t have to. It’s not your job to decide on the best way to reduce MRSA infection or encourage kidney donors. Experts don’t agree, so why should you know the answer?

It’s liberating to realize that your job is simply to write about people, places or institutions that are trying to fix things, using the same critical eye you’d apply to any other story on your beat.

You still need to use data and evidence, however, to decide whether a particular response to a problem is worth writing about. The test isn’t “is this the best solution?” but “is this a good story?”

What about something that’s really new? Fresh is great — but it often comes without much evidence. And programs with lots of clear and persuasive evidence are unlikely to be fresh.

But you can write about an intriguing new idea, even one that has no real evidence, as long as you are clear with the reader about what we know and what we don’t. If there’s not much evidence, you need to show in your story why it’s newsworthy enough to cover anyway.

Look at this story from the Alaska Dispatch News about “Minimum Mike,” a judge in Barrow who has organized his courtroom around the health problems faced by a good number of his defendants: Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Is there any hard evidence that this approach works? Nope, just anecdotes. Is it a great story? Yes it is.

Story Annotation

Alaska Dispatch News

Call him 'Minimum Mike' if you like, but this Barrow judge is trying something new

Kyle Hopkins | October 20, 2016

BARROW -- If you are accused of a crime here, 320 miles above the Arctic Circle, and you can't walk, a wheelchair ramp leads to the swinging courthouse doors. Watch the ice.

If you're accused of a crime and have trouble hearing, ask Donna at the front desk for a special headset. A helper is available to read charges aloud to the blind.

If, like thousands of other Alaskans, you were born with a different, not-so-apparent disability because your mother drank while pregnant, Barrow Superior Court Judge Michael Jeffery has an answer for that, too.

In this courtroom, unlike any other non-specialty court in Alaska, the paperwork handed to defendants is simple and plain. The pace is slow. In a kindly Mr. Rogers voice, Jeffery explains what's happening over and over again and waits for a sign the defendant understands. He writes special instructions telling probation officers and prison officials to take the same thoughtful, unhurried approach.

His goal: Make court comprehensible for teens and adults who suffer lifelong, unfixable brain damage caused by fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

"A person affected by FASD may really be relating to the whole experience like a middle school or far younger student, instead of the high school student or adult that the person appears to be," Jeffery said.

For the past six years a like-minded probation officer in the same courthouse has continued the special treatment when someone who appears to have FASD is convicted.

As judges and law schools look for ways to make the court system equitable for everyone involved a movement called procedural fairness Jeffery developed grass-roots tactics to help people who suffer a disability that suggests a 1-in-3 chance they will one day wind up in prison or jail.

Some people with FASD struggle to understand consequences and are unable to learn from mistakes but benefit from routine and structure. Jeffery emphasizes longer probation and less time behind bars.

To the judge's fans, including national FASD prevention experts, he is a pioneering force for a large but overlooked population of disabled. To some Barrow residents and some local police, he's known as "Minimum Mike."

Jeffery's intentions are good, they say, but criminals need longer prison sentences, not coddling.

Either way, the experiment could come to an end this year.

A different kind of courtroom

On a Sunday afternoon in November, Jeffery took his seat and looked at a nearly empty courtroom. A law clerk settled behind him wearing a flannel shirt and a lumberjack beard.

A shoreline city of Inupiaq whalers and Korean cabdrivers, ice-nerd scientists and blue-collar oilers, Barrow is the capital of the Minnesota-sized North Slope. The sun never sets in the summer and never rises in the winter, and FASD rates are more than twice the statewide figure.

Jeffery saw only two defendants that day, both 18 years old and both accused of underage drinking.

One man stared at the judge, uninterested. The other, Tommy Pikok, studied the paperwork before him, face pale. This was his eighth arrest for minor consuming in four years, he said. Pikok was still sick from two $100 bottles of R&R whiskey the night before.

"You guys have been to court before, so I think you're pretty up to speed on all this stuff," Jeffery said.

He explained what was about to happen anyway. For 15 minutes the judge talked about the basics of the criminal cases the men now faced. He described the difference between a public defender and for-hire lawyers, how defendants must tell the truth about how much money they have, and the fees they might have to pay if convicted.

Pikok, who later said he had been throwing up in his cell all night, pursed his lips. He leaned forward, a mop of hair covering his face. Jeffery hurried to the bottom line.

"Bottom line is, you guys, you can't drink until you're 21."

Moments later, still sitting handcuffed at the defendants table, Pikok vomited into a wastebasket and was allowed to leave the courtroom.

University of Washington researchers estimate that 35 percent of people with FASD in the United States have been to prison or jail. Untold millions in public money could be saved by preventing youth and adults with the disability from being locked up for non-violent crimes or probation violations, yet non-specialty courtrooms across the country make almost no attempt to help defendants with FASD navigate the process.

Except in Barrow.

The same underage-drinking hearing that stretches to an hour here -- a simple first-court appearance on a misdemeanor crime -- might last a few minutes in Anchorage as part of a "cattle call" of afternoon arraignments.

Jeffery later said he usually has no way of knowing for certain if defendants in his courtroom have FASD. He's given up trying to guess. Diagnoses are exceedingly rare, even in Alaska, where health care providers are more aggressive than most in screening for the disability.

When time allows, Jeffery gives everyone his user-friendly version of court. All defendants get the same simplified paperwork.

"I am consciously doing things to try to make a person a little more comfortable and understand a little better by using plain English as much as I can," Jeffery said. "Slowing down, and recognizing that they may need a break, even if normally somebody wouldn't."

Alternatives to prison

Jeffery arrived in Barrow in 1977, working for Alaska Legal Services and seeking a place to practice law where he could learn about another culture. He never left, appointed in 1982 as the region's first and only full-time Superior Court Judge on the North Slope.

A sexual assault case in 1990 convinced Jeffery that special accommodations might be necessary for defendants with FASD. The man accused had been raised by adoptive, sober parents, but the public defender found his birth mother had been an alcoholic. The defense lawyer sought a diagnosis.

Doctors found the man had what was called fetal alcohol effects at the time and is now known as FASD.

"(The public defender's) pitch was it would be manifestly unjust to sentence him without taking this condition into account to try to lower somewhat the jail time and increase time on probation," Jeffery said.

The judge agreed. His attempt to lower the sentence was struck down by a three-judge sentencing panel, however. The Legislature did not allow fetal alcohol syndrome or related disorders to be used to lower a prison sentence, they said.

In 2012, Jeffery championed a change to state law that enabled Alaska judges to do just that. It was the first such law in the United States, Jeffery said.

FASD can now be considered by judges as a mitigating factor when handing down a prison sentence. The exception does not apply to violent crimes committed against a person, like assault, and has not yet been used in a Barrow case.

In the same year the American Bar Association, which represents more than 400,000 U.S. lawyers and law students, passed a resolution calling for more and better screening for FASD within the criminal justice system. Citing the "over-abundance" of children and adults with FASD in foster care, youth court and prisons, the association encouraged lawyers, judges and tribal courts across to country to reduce criminal sentences and look for alternatives to prison for those with the disability.

Jeffery saw the decree as confirmation of his decades-long effort to build an FASD-aware courtroom.

But navigating court hearings is just the beginning. The harder work begins when that person is released on bail or probation and walks back into a world of temptations and choices.

In Barrow, the court system has an answer for that too.

'Mom doesn't talk about it'

Across the hall from Jeffery's courtroom is the office of the sole probation officer for Barrow and seven surrounding villages. Until her recent retirement, the job belonged to a former mental health clinician, Terri Telkamp.

On the day a minor-consuming defendant threw up in Jeffery's courtroom, 78 mugshots covered the wall in Telkamp's second-floor office. Every face is a convicted felon, every one her responsibility. Like Jeffery, Telkamp usually has no diagnosis paperwork that proves a client does or not have some form of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder.

"I can look at the wall and easily, with confidence, say over half. Probably well over half have some affect from some FASD," Telkamp said.

Very few are street-wise, career criminals, she said.

Many people end up in Barrow court for probation violations, not new crimes. Statewide, about 1 in 5 inmates in Alaska is behind bars for breaking probation or parole at a public cost of $35 million a year, according to the Department of Corrections.

Reducing those costs means finding a way to stop people from re-offending, which is a particular problem for felons with FASD.

Those with the disability may struggle to remember instructions. They might be impulsive and easily led, used as accomplices and getaway drivers by more sophisticated criminals.

In response, Telkamp created a daily "breakfast club" meeting for her at-risk probationers who appeared to have some form of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. She would invite them to her office each morning to talk about the day ahead. What were they doing to get their GED? Get a job? Who were they going to hang out with?

The next morning, she'd ask how it went.

"I use concrete language. Simple terms. One of my favorite things is picking up my business card and saying, 'You see these pages and pages of rules? I'm going to put the ones you most need to worry about on the back of my business card, and they're going to fit.'"

Next on her calendar this day was a 23-year-old named Marissa Merly, who had just been sentenced to a year on probation for stealing a handgun. The woman has two small boys of her own and no prior criminal record, but if she doesn't do well on probation she could pay thousands of dollars in fines and spend months in jail.

"It's just going over her head the seriousness of this," Telkamp said.

Merly soon arrived wearing a pink hoodie, coffee in hand. She noticed the photos on the wall and smiled. "I know these people!"

Telkamp showed Merly a binder on her desk labeled "success stories." These are first-person letters written by people just like her who graduated probation, she said. One day Merly could wind up in the binder too.

"This theft crime that you committed, that's not who you really are. ... There's a whole good citizen right here in front of me," Telkamp said.

She launched the speech she gives people new to probation, beginning with the many things Merly can't do for the next 12 months. No alcohol. No drugs. No traveling 50 miles beyond Barrow without permission. No firearms.

That last one can be a problem in a place where many families hunt to fill their freezers and a lookout stands guard at football games to watch for wayward polar bears.

"If it goes boom or bang you can't have anything to do with it," Telkamp emphasized. "I even tell my whalers they can't be the one to shoot the harpoon."

Merly said she doesn't remember taking the gun that led to her arrest. She had shared three or four "fifths" of hard liquor, plus wine, plus beer the night it happened.

In addition to her probation duties, Merly said she is tested regularly by the Native Village of Barrow in order to see her kids. She doesn't know if the boys have an FASD, she said, but she recently flew to Barrow for her own diagnosis.

The doctors told Merly she has fetal alcohol syndrome, she said. "My mom doesn't really talk about it. She just gets mad."

The diagnosis made her sad, Merly said. She dreams of going to college and owning her own home. Regaining custody of her boys.

Telkamp handed her a business card. On the back, the probation officer had written the date of their next meeting and a few ideas she wanted Merly to remember: "Substance abuse treatment." "Restitution." "GED."

A model for elsewhere?

Some of the techniques used by Jeffery and Telkamp might be institutionalized statewide or in specialty courts for people with FASD. Others could be used at a judge's discretion when time allows.

Bail orders, which describe the rules someone must follow while awaiting trial, are scrubbed of legalese and translated into a simple, plain-English checklist in Jeffery's courtroom. ("I cannot drink any alcohol, including homebrew.") Mandatory breaks in the hearing allow new information to sink in.

When listing rules for probation, even the way a sentence is structured can be important, Jeffery said. Sometimes people with FASD do not retain every word said to them. Instead of saying "don't drink," he tells defendants to "stay sober."

Written in large type with a check box to each instruction, Jeffery's orders are four pages long and include instructions like "be drug free" and "let others drive."

Judges must treat all defendants equally, meaning that accommodations made for people FASD must also work for the general population.

Whether other Alaska courts could or should mirror this model of an FASD-friendly courtroom remains unclear.

"It's not as simple as taking our court forms and making them third or fourth-grade reading level, which we should probably be doing for the general public anyway," said Anchorage District Court Judge Stephanie Rhoades.

Motivated by the defendants with mental illness she saw cycling through the court system without understanding their probation conditions or why they were in jail, Rhoades launched the first Mental Health Court in Alaska. The pace and careful consideration of a defendant's ability to understand the proceedings are similar to the way the Barrow courthouse operates.

A small number of Anchorage defendants who have FASD, usually in combination with other disabilities or mental illness, end up there. But in a city where thousands of criminal charges are filed every year, her program can only handle 90 cases at a time.

"The piece of the puzzle that I kind of fit into is, what do you do when you don't have a (specialty) court like that and you're in a community where there is almost no services," Judge Jeffery said. "Then what do you do?"

The Barrow model might work best in similarly small, rural courtrooms where no mental health court is available but a single judge, prosecutor, public defender and probation officer all have a chance to observe the same defendant over time and gauge his or her disability.

Jeffery said he would have to speed through hearings like any other judge if he worked in Anchorage, which is one reason he has stayed in Barrow. Making sweeping changes to the way the court system operates as a whole -- such as hiring "navigators" to help people decipher the rituals and routines of a modern courtroom and prepare for what comes next -- might aid those with FASD but would require energy and funding from state budget writers, Rhoades said.

For now, she said, "It's not a mainstreamed thing to try to address specifically people with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder."

End of an experiment

Not everyone is a fan of the Barrow judge's rehabilitation-minded approach.

"It gets demoralizing. You are putting so many dollars and so many man hours into the investigating and stopping this, and people get slapped on the hand and go about their way," said retiring Borough Police Chief Leon Boyea, describing the department's drug and bootlegging probes.

Telkamp said the prison sentences handed down by Jeffery are in line with Alaska law.

"I know at least a few cases where the police were up in arms because a sentence was too soft, but it was actually the maximum the judge could have given," she said.

At the Native Village of Barrow offices, across town from the courthouse, social services director Marjorie Solomon said the judge and district attorney aren't hard enough on drug dealers. Too many plea deals.

"If it were up to me, they wouldn't be back in the community for a long time," she said.

No criminal case in Barrow has gone to a jury trial since December 2012, Jeffery said. In April 2013, residents held a small protest when a man convicted of the criminally negligent homicide of a 3-year-old girl received a 7-year sentence under a plea agreement.

Resolving the majority of cases by plea bargains makes sense to Jeffery, he said, because it allows for less jail time and more probation in a region that has fewer serious crimes than other rural hubs. North Slope Borough Police Department officers are stationed in every village, dampening violent crime compared to Bush communities with little or no law enforcement, he said.

"And then of course we have these cases which are really bad, and I've handed down some really lengthy sentences," the judge said. In June, he offered as an example, a 45-year-old man received 50 years in prison for first-degree rape.

Although Jeffery would like to remain on the bench, he must step down before he turns 70 in December under mandatory age limits. Telkamp, his unofficial partner in FASD awareness efforts in Barrow, retired in December.

No one has studied Jeffery's courtroom techniques. He will leave the bench unsure of whether his 20-year effort to make a difference in the lives of defendants with FASD is working.

He was compelled to try, he said.

Given what he's learned about the disability, how it creates a range of lifelong impediments, he said, anything less than helping people with FASD understand the complicated steps and high stakes of a criminal hearing would be immoral.

"It really gets down to the ethics of it. Knowing what I know, I have to do it," Jeffery said.

A surprise visit

To Telkamp, the results are obvious.

Among the felons who have passed through Jeffery's courtroom and her probation office is a 23-year-old named James Ahgeak who was arrested in 2012 on a drug possession.

Telkamp suspects many of her clients would not be committing felonies if not for some degree of FASD. Even before she met Ahgeak, she guessed that he was no hardened criminal.

He was in trouble for drugs because, when found staggering along Ahkovak Street drunk one winter night in 2012, he sat beside a police officer and pulled out a bottle of prescription painkillers that didn't belong to him.

"I've got a headache, I don't suppose you'll let me take this will you?" he asked, according to Telkamp.

"That just doesn't make sense," she said. "A streetwise, savvy drug dealer is not going to do that in front of the cop."

On another day, Ahgeak had climbed to the top of a fuel tower outside of town, tied a utility rope around his neck and threw himself down the narrow stairs. A witness called police and North Slope Borough Police Department Sgt. James Michels cut Ahgeak free with a pocket knife. Another 20 seconds and he would have died, Michels said.

Ahgeak has stopped wearing a hood over his head during meetings with probation officers, something Telkamp takes as a good sign. He speaks in flat, friendly tones, and struggled to explain in an interview why he did it.

"I didn't want to live no more, and whatnot," he said.

Ahgeak said he has no idea if his mother drank while pregnant and he has never been tested for FASD. His mother said she was unfamiliar with the disability.

She said she did not drink much during the pregnancy.

Regardless of whether he has the disability, Ahgeak said he liked the judge's kindness. The accountability and encouragement found in daily breakfast club meetings seemed to work for him.

There were missteps. Police once found him drunk in a snowbank, court records show. But Telkamp avoids arresting probationers on first or second violations if they appear to be making progress overall. Relapse is part of recovery.

"(Terri) said that I'm her special one, and whatnot, because I report to her every day," Ahgeak said.

Shortly after the minor-consuming hearings in Jeffery's courtroom and her orientation meeting with Marissa, Telkamp made a surprise visit to Ahgeak's home.

A black-and-white husky named Black Eyes met her at the door. Chicken soup steamed on the stove as Ahgeak's family watched an episode of "NCIS."

As part of probation, Ahgeak agreed to let police enter his house and check for alcohol, drugs or other problems. His parents waited in silence.

James has been doing great, Telkamp told the family. To Ahgeak, she said, "Everybody brags on you when you go to court."

He hasn't been in trouble since.

A Barrow judge's tips for other rural courtrooms

Superior Court Judge Michael Jeffery has spent the past 20 years searching for ways to help defendants with FASD decipher the complicated legal system. Here are his suggestions for other courtrooms in Alaska and across the country:

- When time allows, slow down the hearing. "I take the time to completely explain to local participants what is going on. It is sometimes necessary to take a break in the hearing to allow an individual affected by FASD to process what he or she has heard before yet more information is discussed," Jeffery writes.

- Use clear, concrete language during the hearing. "I try to avoid legal jargon as much as possible. I often use a more informal tone," Jeffery writes.

- Simplify paperwork. When someone is released from jail or prison, they must follow certain rules such as avoiding alcohol, getting treatment or staying away from their victim. Jeffery's forms are written in large type with simple language such as, "The police could arrest me if I do not come back to court or follow all the promises." Unlike at other courthouses, each bail condition has a space for the defendant to initial to show they understand. "The DOC administration in Alaska is interested in this idea, but there is a lot of inertia for 'business as usual,'" Jeffery said.

- Consider third-party custody arrangements for people awaiting trial. Judges can appoint a "third-party custodian" such as a family member to watch over the defendant rather than keeping him or her in jail. Jeffery writes that such arrangements, including electronic ankle monitoring, "Will reduce overcrowding in the jails, are more humane and constructive for defendants affected by FASD, and reduce costs to society."

- Trade jail time for longer probation, when appropriate. In Alaska, a state law championed by Judge Jeffery allows judges to consider an FASD diagnosis as a reason to shorten someone's time in prison if the disability played a role in their crime. "The more people return to (prison), the more familiar it becomes and the harder I think it is to break out of that," said Jeanne Gerhardt-Cyrus, a Kiana-based expert on the disability. "Routine and structure and predictability works for people with an FASD."

Evaluating Evidence

In solutions journalism, there are four ways a response to a problem can become a good story.

- It's a success. Most solutions journalism stories are chosen because something about the response works. The evidence is very clear.

- It's a cool new idea that looks promising. Even if we can't know if a new idea will work on a wide scale, there may be smaller indications - experts love the idea, or it works in a lab or animals (caution here: as we know, curing cancer in mice means we can cure cancer in mice), or it worked in a small pilot study but hasn't been tested on a wider scale. In all these cases, you've got to acknowledge what we know and don't know. And if the track record is weak, indicate why you're reporting on it anyway.

- It's coming here. For example, your city is building an urban bike path to encourage exercise. You'll want to go to another place that's done this and see what about it has worked and what hasn't. That's a story, whether it's a success or not. Better yet, find one that's worked and one that hasn't - and look at what made the difference.

- It's a solution people are talking about, but the discussion could use some rigor. For example: there's lots of hype about health apps - do they really work? Or because apps are all different, here's a better idea: "Health apps: when do they work and when do they fail?"

In all these cases, you'll need to rely on evidence to determine what's working. For health reporters, this is familiar territory. We find and evaluate evidence to decide how to report on clinical studies, drug trials, and rating systems for hospitals and doctors, among many other topics.

The process is similar for solutions stories. A program claiming to reduce infant mortality by 38 percent over five years - how do you evaluate that claim?

It is no more difficult to vet a solutions story than a problem-focused story. What's different is the perceived consequence of getting it wrong. Get a problem story wrong and that's a journalistic misdemeanor. Get a solutions story wrong and that's a felony. That's not how the outside world sees it. But to journalists, there's nothing worse than looking gullible.

The most important step towards getting it right is to be conservative in your language. Don't over-claim. Just report what the evidence says. Nothing is perfect, and the more we reflect this reality, the more our audience will trust us.

But "what the evidence says" can be a complex question. For example, Leapfrog, Consumer Reports, HealthGrades and U.S. News & World Report - plus CMS Hospital Compare - all publish ratings of hospitals. Not a single hospital scores highly in all the rankings. That's because they all weight and value different things. Leapfrog, for example, measures how well hospitals keep patients from harm, while HealthGrades looks at death or complications outcomes from 27 different clinical procedures. We all know to be wary of self-reported claims of success on an organization's website. But the conclusions of research papers in prestigious peer-reviewed academic journals can also be misleading or wrong - and many of these studies can't be replicated.

- Consider the source. Is the data published and where? Who's measuring the outcome? Is it a source you trust?

- Understand the statistics. You should have a basic grasp of the data the researchers collected and how they manipulated it. If you don't speak statistics, try Khan Academy.

- Look at what's being measured. Some ways this can mislead: A hospital or doctor's office may get very high marks from patients - but that's likely to reflect waiting times and staff courtesy, not health outcomes. Some researchers will report success among a subgroup - but fail to report that the intervention had no effect on the total group.

- Be mindful of the pressures to report success. Researchers have no incentive to discover that something doesn't work, and plenty of incentive to find that it does. This creates bias - conscious or unconscious - towards interpreting results in the best possible light.

- Cui bono? "Who gains?" is always a key question. One example: some organizations that rate health care providers make money from the providers they rate.

- Seek independent expert opinion. Ask experts not involved in the program if the numbers make sense.

Data Resources

If you're a health reporter, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Data Navigator needs no introduction. (It does need a designer, though.)

The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation's charts can tell you where each U.S. county ranks on obesity, binge drinking, and deaths from just about every cause you could think of. IHME also hosts the Global Burden of Disease report, a staggeringly complex project that assembles data on causes of death and disability from everywhere in the world into easy-to-use visualizations. IHME's staff can also answer specific queries.

County Health Rankings shows where counties stand on air quality, tobacco use, access to care and other issues that affect health.

Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care uses CMS Medicare data to compare and rank hospitals and regions on readmission rates, percent of end-stage patients who die in the hospital, use of the health care system and many other issues. Easier to use than CMS, but covers a limited number of topics.

There are also topic-specific public databases on every issue in every state. (The quality is better in some places than others.) Here's a few from New York State to give an idea.

And here are some places to get not health data, but information about health data:

- Health News Review reviews news stories and press releases on health for accuracy, and has toolkits to help you analyze studies.

- Retraction Watch tracks retractions of scientific papers.

- This tip sheet from ProPublica's Charlie Ornstein tells you how to read CMS data - and why it's such an exciting time to be a health journalist!

- Clear Health Costs has data on what providers charge for common elective health procedures - and crowdsourced information on what people actually pay.

The positive deviant

When journalists get hold of one of the above databases, or any other data set, it's our instinct to look for the worst performer - and pounce. When a new report comes out on hospital c-section rates, for example, journalists will usually focus on the local hospital that's doing the worst. But that story would be stronger if we also included the local hospital that's doing the best, and examine how it achieved those results.

A positive deviant is someone, somewhere or something that's getting better results with the same resources. That last part is important. You'd expect the wealthy New York City suburbs of Westchester County to do a lot better on health indicators than Bronx County, the poorest urban county in America. That doesn't make Westchester a positive deviant. On the other hand, if Westchester was doing only a little better than the Bronx on a particular indicator, then it's the Bronx that could be a positive deviant: What did this poor county do to pull almost even with the rich ones?

This story looks at how one of the poorest countries in Maine became one of the healthiest - a textbook positive deviant. (Spoiler: Sending nurses to people's homes was key.)

Positive deviant stories don't have to be about stellar health outcomes. They can cover great improvement as well. One example is a story by Stephanie O'Neill of KPCC about Riverside Hospital, which greatly reduced its hospital-based infections, going from "unacceptable" to "average." Riverside still ended up at the middle of the pack - but how it climbed there from the bottom is a good positive deviant story.

Databases and rankings are an easy source of positive deviants. If you consider the database trustworthy enough to be the source of a problem-focused story, you can trust it for a solutions story as well.

But you can find positive deviants in other ways. At WAMU public radio in Washington, D.C., the seed for a solutions series was planted when an editor drove by a mental health center that was emblematic of the capital area's problems with mental health treatment and had been shuttered in 1991. She asked herself, "I wonder what's happened since?" The team found a United Cerebral Palsy study saying that Washington had risen from one of the worst places in the nation for people with physical and developmental disabilities to one of the best. That's a form of a positive deviant story.

How did that happen? "Since this story was a big mix of history and current policy, I tried to approach it in a linear fashion," says WAMU reporter Martin Austermuhle. "I sought out and interviewed important historical figures and actors that could help me build the timeline from start to finish, and once that was done I circled back to people in the policy world to tell me both how things used to be done, how they are done now and how D.C. compares to other places in the country on implementing good policies."

The resulting four-part series, "From Institution to Inclusion," won positive feedback from listeners, including those who said they'd been interested to hear what resulted after the discovery of the initial horrific problems. It won praise from people with disabilities and their advocates, as well as the 2016 Katherine Schneider Journalism Award for Excellence in Reporting on Disability.

Positive Deviants

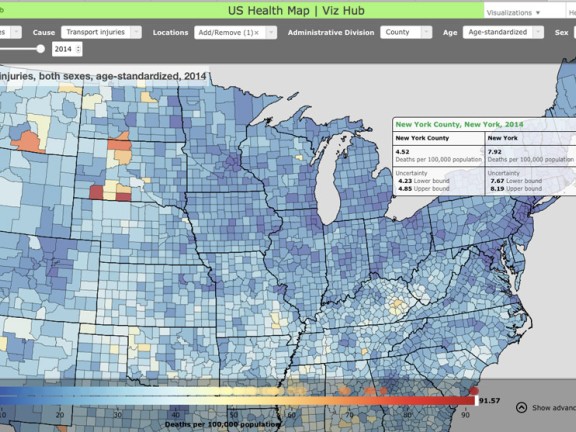

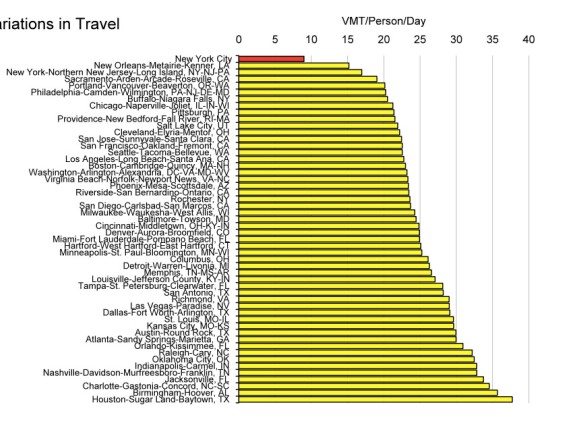

These five screenshots shows how to use the concept of positive deviance to tell a series of revealing stories about a major killer in the United States - transport deaths.

Chart One looks at Transport Deaths per 100,000 people. Ranked number one is New York County - Manhattan. (You have to look at the line across the bottom to see that New York's 4.52 deaths per 100,000 people is indeed the lowest.)

Is Manhattan a positive deviant? Are its residents the safest drivers in the United States?

Well, if you look at other statistics, it turns out that Manhattanites got their top ranking only because they rank at the bottom on how much people drive. That's another way New York County is a positive deviant.

Chart Two is Vehicle Miles Traveled per Person per Day. This shows that New Yorkers drive far fewer miles than residents of any other major city in the United States. If you take this into account, New Yorkers aren't necessarily great drivers - they just drive far less than anyone else. Drive less, and you have fewer traffic fatilities per person. If the Transport Deaths chart was per mile driven and not per person, Manhattan would come out much worse.

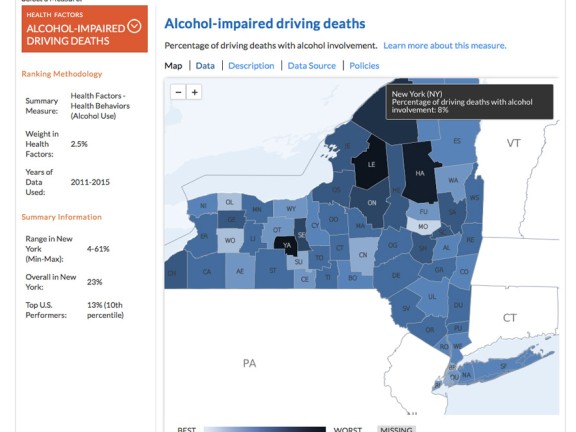

Chart Three, Alcohol-Impaired Driving Deaths, shows another possible factor contributing to New York County's safe driving record. Manhattan is a positive deviant this way, as well. Alcohol-related deaths are a very small percentage of traffic fatalities in Manhattan-just 8 percent.

The chart shows counties in New York state only, but you can see the pattern-urban New York City (Kings, Bronx, Queens and New York counties) counties had low rates of alcohol-related deaths as a percent of traffic deaths, and Manhattan had the lowest. (There were two other counties in New York state with lower rates, but these were tiny, with few traffic deaths and only one alcohol-related death. So these are statistical quirks.)

Why so few alcohol-related deaths? Because much of the time when a Manhattanite is in a car, he's not driving; a (presumably) sober professional is. The low rate of car ownership and high use of taxis and public transport mean that no one has to wrestle the car keys out of the hands of someone who's had too many margaritas. She likely never had any keys to begin with. Since alcohol-related deaths are a big part of overall transport fatalities, this is another reason for Manhattan's top ranking.

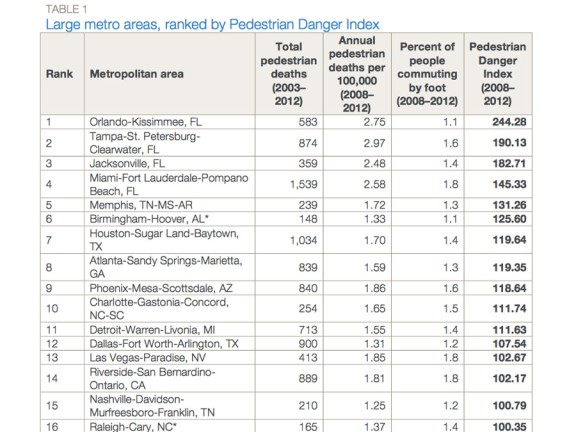

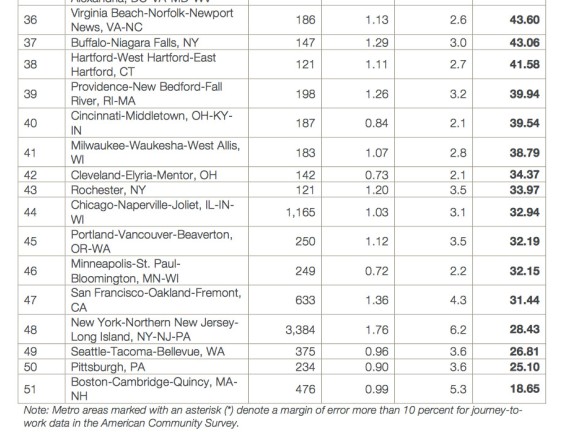

And the last way Manhattan is a positive deviant can be seen in Chart Four and Chart Five, both from the Pedestrian Danger Index. The most dangerous cities for walkers-starting with Orlando, Tampa, Jacksonville, Miami and Memphis-are Sunbelt cities where very few people walk. That's not a coincidence. Sunbelt cities were constructed to allow cars to go fast-and that's dangerous.

Northern cities such as New York and Boston, by contrast, were built before cars existed. So they were constructed for pedestrians, public transport and, umm, horses. Cars were an afterthought. They can't go very fast, and therefore they kill fewer people.

Kyle Hopkins is special projects editor of the Anchorage Daily News. Follow him on Twitter @kylehopkinsAK.